O Empreiteiro percorre quase 1 mil km da estrada e relata a precariedade do trecho e os problemas da região onde o agronegócio tem papel decisivo na economia brasileira

Augusto Diniz – Guarantã do Norte (MT)

Poucos trechos em boas condições, boa parte do asfalto desgastada e esburacada devido ao intenso tráfego pesado e extensos intervalos de estrada quase impraticáveis por causa da lama. Esse é o quadro da Cuiabá (MT)-Santarém (PA), na BR-163, a rodovia cuja pavimentação, prometida para final de 2014, tem sido a mais aguardada no País.

A revista O Empreiteiro percorreu quase 1 mil km dos 1.780 km de estrada entre as duas cidades, no trecho que, inicialmente, será o mais beneficiado com a ligação completa por asfalto das ricas terras do agronegócio em Mato Grosso ao porto fluvial de Santarém, às margens do rio Tapajós, um dos principais afluentes do Amazonas, para escoamento da produção.

O estado mato-grossense é responsável por 24% da produção nacional de grãos e seu rebanho é de 28 milhões de cabeças de gado, cerca de 10% da criação nacional, com perspectivas de crescimento expressivo nos próximos anos dos diversos itens do agronegócio, de acordo com dados da Companhia Nacional de Abastecimento (Conab).

Hoje, a maior parte dos caminhões que transporta grãos (notadamente milho e soja) produzidos no norte do Mato Grosso, ainda ruma em direção ao portos de Santos (SP) e Paranaguá (PR), para escoar a produção. Essa operação aumenta em cerca de 1 mil km o trajeto, o que já não aconteceria se a carga fosse descarregada no Norte do País. Sobrecarrega, portanto, as já congestionadas rodovias do Sul-Sudeste, ameaçando de colapso os principais terminais portuários brasileiros e, principalmente, encarecendo seu transporte.

Percurso

O Trevo do Lagarto, em Várzea Grande, na região metropolitana de Cuiabá, dá a dimensão do quanto o tráfego de caminhões poderia ser amenizado se a ligação por asfalto para Santarém já estivesse concluída. É que por ali passam todos os veículos de carga que descem do chamado Nortão mato-grossense para o Sul do País.

O grande movimento de carretas, principalmente nesse período pós-colheita da safra de grãos (junho), cria uma fila quase contínua de veículos até Sinop, a 500 km de Cuiabá e principal cidade cortada pela BR-163, até Santarém.

O começo da estrada, em via de mão dupla, já dá uma ideia dos problemas que serão encontrados dali para frente em alguns longos trechos: falta de acostamento, asfalto virando pó, buracos e depressão e sinalização vertical e horizontal precárias – algumas cobertas pelo mato às margens. Pedaços de pneus estourados também são uma constante no acostamento perigoso.

Mas justiça seja feita: no início, alguns trechos estão com trabalhos de recapeamento e outros com operação tapa-buraco em andamento.

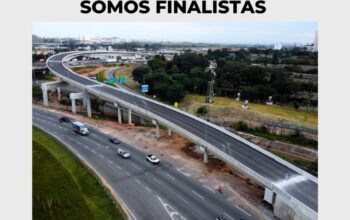

Cerca de 120 km depois de deixar Cuiabá, em Rosário do Oeste, são vistas na estrada obras de viaduto que cruza a cidade e o início do trecho em pista dupla, com canteiro central. A pista dupla é interrompida em alguns momentos, já que a duplicação encontra-se em obras em várias partes da rodovia até Posto Gil, o que significa ainda trafegar em via de mão dupla.

De Rosário do Oeste a Posto Gil tem aproximadamente 50 km. Além de Rosário do Oeste, outros dois viadutos de grande porte estão sendo construídos em Nobres e Posto Gil. As obras para sobrepor a rodovia, porém, são vistas como desnecessárias para algumas pessoas ouvidas durante a viagem. É que nas mais movimentadas cidades da estrada, como Sinop e Sorriso, o expediente não foi utilizado, nem por isso ambos os municípios têm problemas de congestionamento em seus respectivos perímetros urbanos. Nessas localidades foram construídos apenas pontilhões.

A partir de Posto Gil, a estrada volta a ser exclusivamente de mão dupla – pelo Plano de Investimento em Logística do governo federal, anunciado ano passado, a duplicação deve seguir até a cidade de Sinop. Também é a partir dessa localidade que ccomeçam as extensas plantações de grãos a perder de vista no horizonte. O asfalto continua com problemas, assim como a falta de sinalização e acostamento, mas verificam-se intervenções mais intensas de recapeamento e reforma nas pistas.

Força do agronegócio

É pela rodovia que se constata também a pujança do agronegócio nas prósperas cidades de Nova Mutum, Lucas do Rio Verde, Sorriso e Sinop, todas planejadas, ocupadas por grandes armazéns de granéis de um lado e do outro pela área urbana central organizada. Todas possuem acessos com pista dupla da BR-163 em seus respectivos trechos urbanos.

Depois de Sinop, o movimento de caminhões e carros cai drasticamente. É que a produção de grãos entra em declínio e as propriedades dão espaço aos pastos. Como parte expressiva dos caminhões graneleiros usa a rodovia no sentido contrário para escoar a produção, não se justifica, atualmente, o tráfego intenso de caminhões nesse trecho.

Ao longo das margens da rodovia são observados, então, animais silvestres mortos. E por ali avultam buritis e castanheiras, árvores típicas da Amazônia. O menor tráfego faz a estrada apresentar melhores condições de uso, com asfalto menos desgastado e poucos buracos.

Em direção ao norte, surgem Itaúba, Peixoto de Azevedo (lojas oferecendo equipamentos para garimpo e outras comprando ouro denotam local de exploração mineral), Matupá (com concentração de grandes frigoríficos às margens da rodovia) e Guarantã do Norte, última cidade de Mato Grosso antes de ingressar no Pará, a cerca de 750 km de Cuiabá, e local onde chegou o asfalto na rodovia há apenas quatro anos.

Pontes de madeira

Dali até a divisa daqueles estados são 50 km. E a Serra do Cachimbo desponta como o marco da transição do cerrado para a Florest

a Amazônica. O asfalto da Cuiabá-Santarém termina em uma precária ponte de madeira na divisa de Mato Grosso com o Pará. Para frente, já em território paraense, são 40 km de estrada de terra e lama ou com restos de algum tratamento asfáltico em meio à selva. Veem-se obras em andamento em pequenos trechos desse precário percurso.

Mais adiante, volta o asfalto à rodovia, em área do município de Altamira, depois de quase 1 mil km de viagem.

De acordo com a Associação dos Produtores de Soja e Milho (Aprosoja), que fez um levantamento recente das condições do trecho entre a divisa de Mato Grosso e Pará até Santarém (PA), dos cerca de 1 mil km de estrada, mais de 400 km ainda são de terra ou estão com obras de terraplenagem e regularização do subleito ou revestimento asfáltico em andamento. A entidade reclama de falta de sinalização, drenagem subterrânea e pontes inconclusas no trajeto, além da apresentação de problemas na pavimentação em trechos já asfaltados.

José Silva, motorista de uma carreta bitrem carregada com 37,5 t de soja, diz que faz o trajeto de Sinop para Santarém desde o ano passado. São quatro dias de viagem.

O pior trecho, segundo o caminhoneiro, é entre Rurópolis e Santarém. “Existe 170 km de chão muito ruim”, conta. Os caminhões saem em comboio rumo ao porto no Pará. A viagem à noite é interrompida por conta do perigo de tombar a carga.

A volta da viagem não tem retorno com outros produtos, como acontece, em geral, de quem vai para o Sul. Mas José Silva diz que a estrada melhorou do ano passado para cá e que prefere dirigir até Santarém a ir a Santos ou Paranaguá. “A estrada depois de Cuiabá (rumo ao Sul) é muito movimentada, com vários pedágios, caminhões demais e ainda tem fila para descarregar”, relata.

Estradas vicinais

Ao longo da Cuiabá-Santarém, principalmente no trecho que corta o cinturão dos grãos, entre Nova Mutum e Sinop, há estradas vicinais asfaltadas e mantidas por produtores rurais em convênio com o governo do estado e municípios. Algumas delas são pedagiadas.

Referidas vias ligam a BR-163 a cidade menores fora do eixo rodoviário principal, mas que são estradas de escoamento de produção.

No caso das concedidas, a gestão da rodovia fica por conta de uma acordo assinado entre o governo do estado e a associação de produtores locais participantes do consórcio.

Cuiaba-Santarem highway’s incomplete paving is evidence of negligence

The O Empreiteiro magazine rides almost 1 thousand km on the highway and reports how precarious the stretch is and the problems in the region where agribusiness has a decisive role in the Brazilian economy.

A few stretches in good conditions, a significant part of the asphalt layer worn out and full of holes due to the intense heavy traffic and long road intervals almost impossible to drive on due to the mud.

The O Empreiteiro magazine rode almost 1 thousand km out of the 1,780 km of the road between the two cities, a stretch that initially would benefit from that complete connection duly paved, linking the rich lands of agribusiness in Mato Grosso to the river port in Santarem, on the banks of the Tapajos River, one of the main contributors of the Amazonas River, to drain the production.

Mato Grosso state is responsible for 24% of the Brazilian production of grains and cattle composed of 28 million heads, about 10% of the Brazilian contingent, with perspectives of expressive growth in the next years of the several items of the agribusiness, according to date of the National Company of Supply (Conab).

Today, most of the trucks carrying grains (particularly corn and soybean) produced in the north of Mato Grosso, still oriented towards the ports of Santos 9SP) and Paranagua (PR), to drain the production. That operation increases about 1 thousand km in the way, which would not happen if the cargoes were unloaded in the north of the country. It overloads, therefore, the already crowded roads in the South-Southeast, thus threatening with collapsing the main Brazilian port terminal and mainly overloading the transportation.

The route

The Trevo do Lagarto in Varzea Grande in the metropolitan region of Cuiaba, gives us the dimension of how much the traffic of trucks could e softened if the road to Santarem were well paved and had already been complete. The problem is that there all cargo trucks coming down from the so-called “Big North” of Mato Grosso pass traveling towards the south of the country.

The significant traffic of large trucks, mainly in the period of after the harvest of the grain crops (June) creates a continuous line of trucks as far as Sinop, 500 km far from Cuiaba and the main city cut by the BR-163 highway, and as far as Santarem.

The beginning of the road, with double lanes, already gives us an idea of the problems to come as from there in some long stretches: lack of shoulders, powdering asphalt, holes and depressions and precarious vertical and horizontal signage – some covered with weeds from the road sides. Pieces of blown-up tires are also something we constantly find in the dangerous sides of the road.

But something has to be said: at the beginning, some stretches have been recovered and others have ongoing hole-covering operations.

Approximately 120 km after leaving Cuiaba, in Rosário do Oeste, there are jobsites for a viaduct that crosses the city and the beginning of the stretch with double lanes with an island in the middle. The double lanes are interrupted sometimes once the duplication of the work in under construction in several parts of the highway as far as Posto Gil, which means that we could still ride on double lanes.

From Rosário do Oeste to Posto Gil there are approximately 50 km. In addition to Rosário do Oeste, other two large viaducts are being built in Nobres and Posto Gil. The works for the roads over the road are deemed unnecessary by some people heard during the trip, though. Trouble is that in the more populated cities served by the highway, such as Sinop and Sorriso, no viaducts have been planned, and, nevertheless, both cities do not have problems related to traffic jams within their respective urban perimeters. At hose locations only foot bridges were built.

As from Posto Gil the road has double lanes exclusively – according to the Plan of Investment in Logistics of the federal government announced last year, the duplication should g

o on as far as Sinop. It is also as from that location that extensive grain plantations start, which go as far as the horizon. The asphalt has still problems, as much as lack of signage and shoulders, but there are some more intense interventions of paving and remodeling the lanes.

The agribusiness’ strength

It is through the road that we can also see the strength of the agribusiness in the prosperous cities of Nova Mutum, Lucas do Rio Verde, Sorriso and Sinop, all of them planned and occupied by large warehouse of grain in bulk on both sides of the central organized urban area. All have accesses with double lanes from BR-163 and their respective urban stretches.

After Sinop, the traffic of trucks and cars drops drastically. That is so because the grain production is reduced and the properties are substituted with grazing areas. As an expressive part of the grain trucks use the road in the opposite direction to drain the production, currently it is not justifiable any intense traffic of trucks in that part of the road.

Along the sides of the road we could then see dead wild animals. And there are many murity palms and chestnuts, typical trees of the Amazon. Once there is less traffic, the road is in better conditions, with less worn out paving and just a few holes.

Going to the north, there are Itauba, Peixoto de Azevedo (stores offering mining equipment and other where gold is bought, which show that it is a mineral exploration area), Matupá (with a concentration of large meat companies on the margins of the road) and Guarantã do Norte, the last city in Mato Grosse before we enter in Pará state, about 750 km far from Cuiabá, and where the road was paved just four years ago.

Wooden bridges

As from there to the border of those states there are 50 km. And in Serra do Cachimbo we can have a glimpse of the transition of the dense vegetation with twisted trees to the Amazon Forest. The pavement of the Cuiaba-Santarem road ends in a precarious wooden bridge on the border of the Mato Grasso and Para state. As from there, already in Para, there are 40 km of dirt and mud roads or covered with some asphalt treatment in the middle of the jungle. There are ongoing jobsites in small parts of that precarious route.

Farther ahead, there is asphalt covering the road again, in the area of the city Altamira, after almost 1 thousand km.

According to the Association of Soybean and Corn Producers (Aprosoja), which has recently made an assessment of the conditions of the road between the Mato Grosso and Para border as far as Santarem (PA), out of the approximately 1 thousand km of road, over 400 km are still dirt road or have earthmoving and the road sub-bed being corrected, or are being paved. The association complains against the lack of signage, underground draining and unfinished bridges in the road, in addition to problems in the parts already paved.

José Silva, a driver of a double track loaded with 37.5 t soybean, says that he has driven from Sinop to Santarem since last year. Four trips a day.

The worst part, according to that truck driver, is between Ruropolis and Santarem. “There are 170 km of dirt in very bad status”, tells he. Trucks drive in a convoy towards Para port. The trip is made at night and it is interrupted due to the danger of having the cargo fall.

In the trip back the trucks are not loaded with other products, as it is usual, from those going to the south. But Jose Silva says that the road has improved since last year and that he prefers to drive as far as Santarem than to go to Santos or Paranagua. “The road after Cuiaba (towards the south) has heavy traffic, with several toll booths, too many trucks and also there are lines to unload the truck”, he reports.

Vicinal roads

Along the Cuiaba-Santarem road, mainly in the part that cuts the grain area, between Nova Mutum and Sinop, there are paved vicinal roads kept by rural production under agreement with the state and municipal governments. Some of them have toll-booths.

Those roads link the BR-163 to smaller cities out of the main road axis, but they are roads to drain production.

In the case of roads under concession, their management is done under an agreement signed by the state government and the local producers association which participate in the consortium.

Fonte: Revista O Empreiteiro

O Empreiteiro percorre quase 1 mil km da estrada e relata a precariedade do trecho e os problemas da região onde o agronegócio tem papel decisivo na economia brasileira

O Empreiteiro percorre quase 1 mil km da estrada e relata a precariedade do trecho e os problemas da região onde o agronegócio tem papel decisivo na economia brasileira